Robotics Beginnings — From Ancient Dreams to Revolution - Part I

📖 Hey Thinkers!

Welcome to a special deep-dive into one of humanity’s most fascinating technological journeys – Robotics. From Leonardo da Vinci’s mechanical sketches to General Motors’ assembly lines, the story of robots is a testament to human innovation, imagination, and the relentless pursuit of automation.

This week, we’re exploring how it all started and the groundbreaking achievements that shaped the robotics industry as we know it today.

🏛️ The Ancient Roots: Humanity’s Obsession with Automation (400 BC - 725 AD)

Long before the Industrial Revolution, ancient inventors were already dreaming of machines that could move, think, and work autonomously. What’s remarkable is that many of these dreams weren’t fantasy—they were real machines built with the technology of their time.

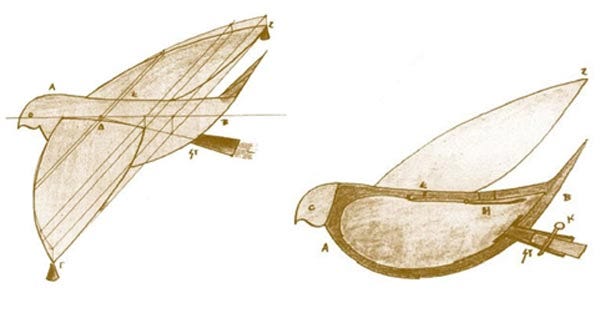

The First Flying Robot: Archytas’s Steam-Powered Pigeon (~400 BC)

Let’s start with something extraordinary: the world’s first self-propelled flying device.

Archytas of Tarentum (428-347 BC), an ancient Greek mathematician, inventor, and philosopher, created something that wouldn’t be replicated for over 2,000 years—a wooden, steam-powered pigeon that could actually fly.

Key Details:

Constructed entirely from wood

Powered by steam or compressed air (accounts vary)

Could fly several hundred meters

First-ever autonomous flying machine

Why It Matters: Archytas designed the pigeon as a toy to entertain children, but its significance was far greater. He proved that machines could harness energy to create motion—a foundational principle of all robotics.

Historical Context: Archytas was also the inventor of the pulley and the screw, mechanical systems that became the backbone of industrial machinery thousands of years later.

Modern Reflection: When you watch a drone or robot quadcopter today, you’re witnessing the spiritual descendant of Archytas’s pigeon—the dream of autonomous flight finally perfected.

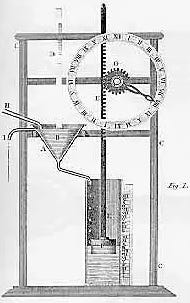

The First Automatic Self-Regulating Device: Ctesibus’s Water Clocks (~270 BC)

Ctesibus of Alexandria, a Greek inventor and physicist, created something revolutionary: the first device with negative feedback regulation—the ancestor of all automatic control systems.

How It Worked:

A large reservoir filled with water

A precise hole in the bottom allowed water to drain at a constant rate

The water level was marked into 24 equal divisions

As the water drained uniformly, the divisions marked the hours

A float connected to gears would maintain constant flow rate

Why It’s Groundbreaking: This was the first device that could maintain stability automatically. It didn’t require human intervention—it regulated itself. This principle—feedback loops that enable self-regulation—is the core of all autonomous systems today, from thermostats to robotic balancing systems.

Modern Applications:

Cruise control in cars

Temperature regulation in HVAC systems

Robot balance systems (like Boston Dynamics’ Atlas maintaining upright posture)

Industrial manufacturing quality control

The Insight: Ctesibus proved that machines could be intelligent without being conscious—they could make autonomous decisions based on sensory feedback. That’s the essence of modern robotics AI.

The Antikythera Mechanism: Ancient Computing (77-100 BC)

In 1901, a diver discovered something that rewrote our understanding of ancient technology. Between the Greek islands of Crete and Kythera, he found a corroded bronze device that would captivate scientists for over a century.

The Antikythera Mechanism is often called the world’s first analog computer.

What It Was:

A complex system of at least 30 bronze gears

The size of a large book

Encased in wood with multiple dials on the front and back

Dated to around 100 BC

What It Did:

Calculated the positions of the sun, moon, and planets

Predicted solar and lunar eclipses

Tracked the ancient Olympic calendar

Was incredibly accurate—off by only about 1% in its calculations

Why It’s Shocking: The Antikythera mechanism represents a level of mechanical sophistication that wasn’t replicated anywhere else in the ancient world. Historians were astounded—how did the Greeks create something so advanced?

Modern Reverse Engineering: In 2006, scientists used CT scans and 3D modeling to understand its mechanisms completely. It turns out the gearing system was extraordinarily elegant—using differential gears (gears that hadn’t been “officially” invented until the 1600s).

Historical Mystery: The device was likely created for an ancient Greek astronomer or wealthy patron. Over 100 such devices probably existed, but only fragments survived. The sudden disappearance of this technology after the fall of the Roman Empire remains one of history’s great puzzles.

Key Insight: Robotics and computing aren’t modern inventions—they’re as old as human civilization’s desire to create machines that can think and calculate.

Hans Bullmann: The First Real Androids (1525)

In Nuremberg, Germany—a city that would become the heart of mechanical innovation—Hans Bullmann created something extraordinary: the first real androids in human form.

What Made Them Special:

Designed in the exact proportions of human beings

Some could play musical instruments

Mechanically sophisticated enough to perform complex movements

Crafted with the precision of Renaissance artistry

The Surviving Artifact: One of Bullmann’s most famous creations was a woman lute player. This mechanical maiden could move her fingers, arms, and body in a coordinated performance. Remarkably, this 500-year-old android survived and is now housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, where it remains a testament to Renaissance engineering.

Historical Significance: Bullmann wasn’t just building curiosities—he was solving real mechanical problems: How do you transmit rotational motion? How do you create synchronized movements? How do you make a machine move with grace rather than just brute force? These questions would occupy engineers for centuries.

Johannes Müller: Flying Machines (1533)

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (also known as Regiomontanus), a German mathematician and inventor, pushed the boundaries of what was mechanically possible.

His Creations:

A mechanical eagle made from wood and iron that could move and potentially fly

A mechanical fly that demonstrated precise mechanical articulation

Context: Müller was working in an era when the very idea of machines achieving locomotion was revolutionary. His mechanical eagle wasn’t intended as a weapon or tool—it was a proof of concept. If you could make a bird move, you could make anything move.

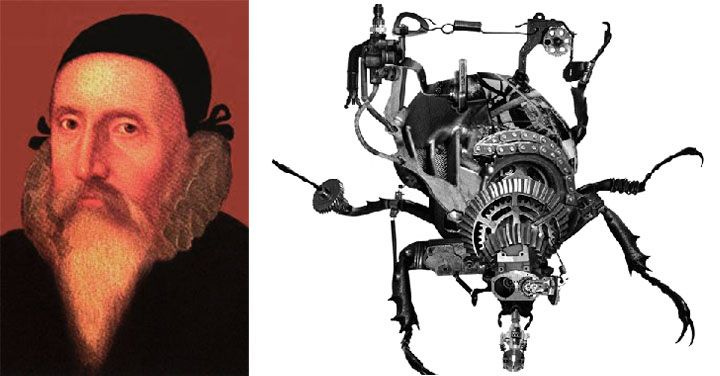

John Dee’s Flying Beetle (1543)

In England, John Dee, a famous astrologer, mathematician, and inventor, created a wooden beetle that could fly.

The Significance: What’s remarkable about Dee’s beetle is that it represented a different approach to the problem of flight. While Müller built a large eagle, Dee engineered a smaller, more intricate mechanism. This teaches us something important: there are multiple solutions to the same problem. The diversity of approaches by different inventors would later accelerate innovation.

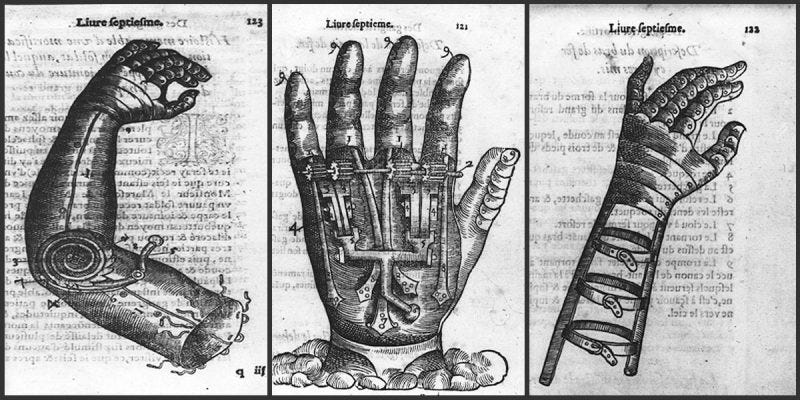

Ambroise Paré: The Prosthetic Revolution (1564)

French surgeon Ambroise Paré published his surgical treatise, Les Oeuvres, which included something groundbreaking: detailed illustrations of mechanical limbs.

What He Documented:

Two mechanical hands

One mechanical arm

One mechanical leg

Internal mechanisms shown in precise technical drawings

Why This Matters: Paré wasn’t just documenting existing prosthetics—he was advancing prosthetic design. His work bridged surgery and engineering, showing that mechanical limbs could restore function to injured people. This principle—robots as prosthetics, robotics as medicine—would become increasingly important in the 20th century and beyond.

Modern Parallel: Today’s prosthetic robotics, from bionic limbs to exoskeletons, trace their conceptual lineage directly back to Paré’s work.

🎼 The Era of Performance Automata (1738-1810)

Jacques de Vaucanson: The Duck (1738)

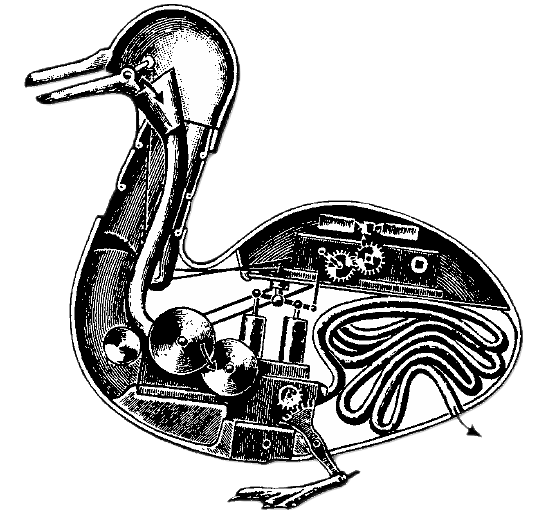

Jacques de Vaucanson, a French inventor and showman, created what might be the most famous automaton ever built: “The Duck”—a copper mechanical bird with extraordinary capabilities.

What The Duck Could Do:

Sit and stand

Flap its wings with realistic motion

Eat (it would consume grain)

Drink water

Defecate (yes, really—proving the food was being processed)

Splash around in water like a real duck

The Engineering Marvel: The wings alone contained over 400 moving parts. Creating that level of mechanical complexity required not just genius but years of experimentation.

Before The Duck: Vaucanson’s first creation was a flute player—an automaton that could play 12 different songs by manipulating a real flute. This was remarkable because it proved you could program complex musical performances into mechanical systems.

Why It Matters: Vaucanson understood something crucial: automation isn’t about speed—it’s about replication of behavior. His automata didn’t work faster than humans could work. But they could work continuously and reliably, and they could perform in public for entertainment.

Legacy: Vaucanson’s work influenced generations of inventors. His principle—that machines could replicate human and animal behavior for public consumption—would eventually lead to theme parks, animatronics, and entertainment robots.

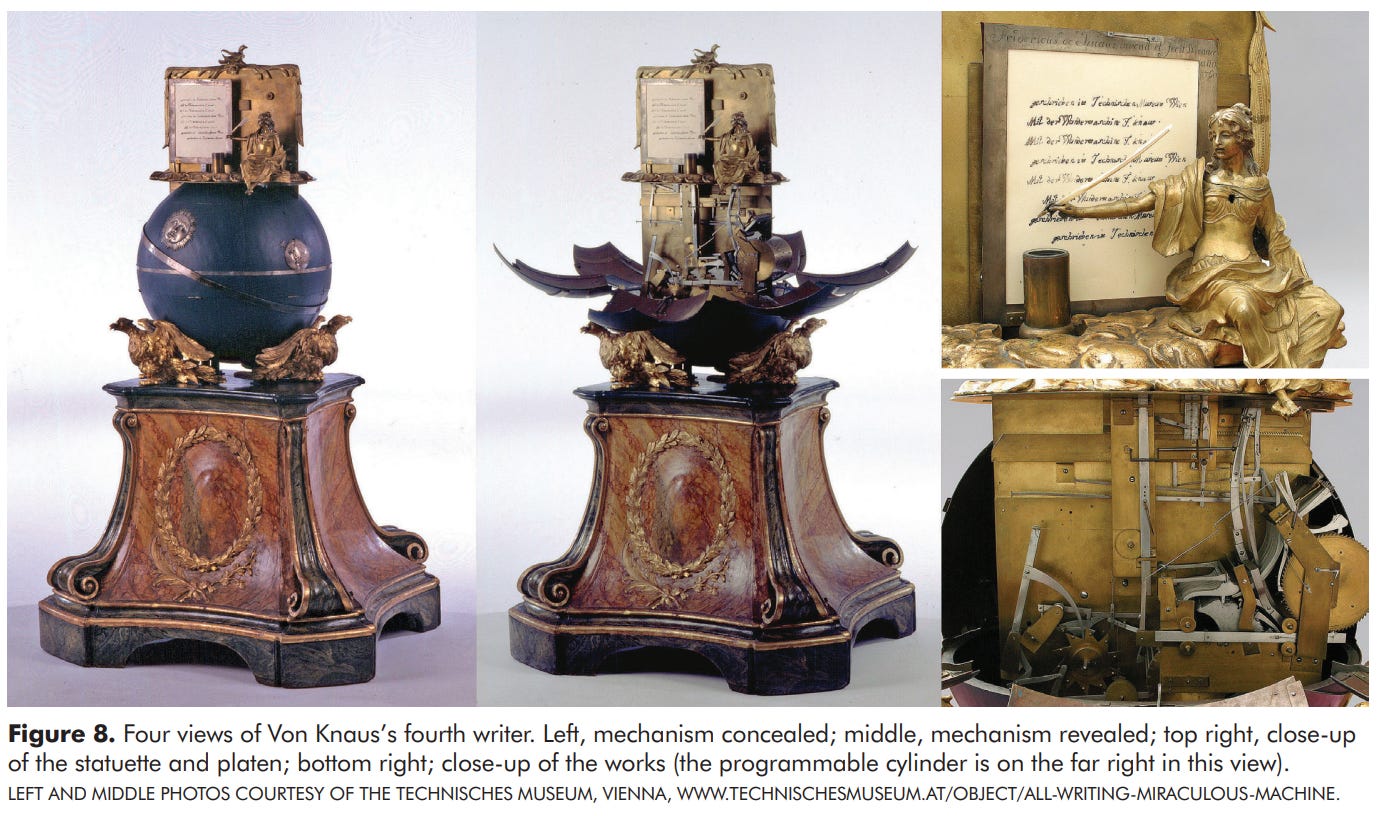

Friedrich von Knauss: The Writing Machine (1760)

German inventor Friedrich von Knauss created an android that could hold a pen and write up to 107 words.

The Challenge Solved: Writing is far more complex than playing music or pretending to eat. You need:

Precise hand control

Proper grip strength

Finger articulation

Arm movement coordination

The ability to form letters accurately

The Achievement: Von Knauss solved all of these problems mechanically. His android could write anything—not a pre-programmed phrase, but whatever you wanted, within its 107-word capacity.

What This Represents: This was programmable robotics before computers. By adjusting the mechanical settings, you could make the android write different things. It was the mechanical equivalent of software.

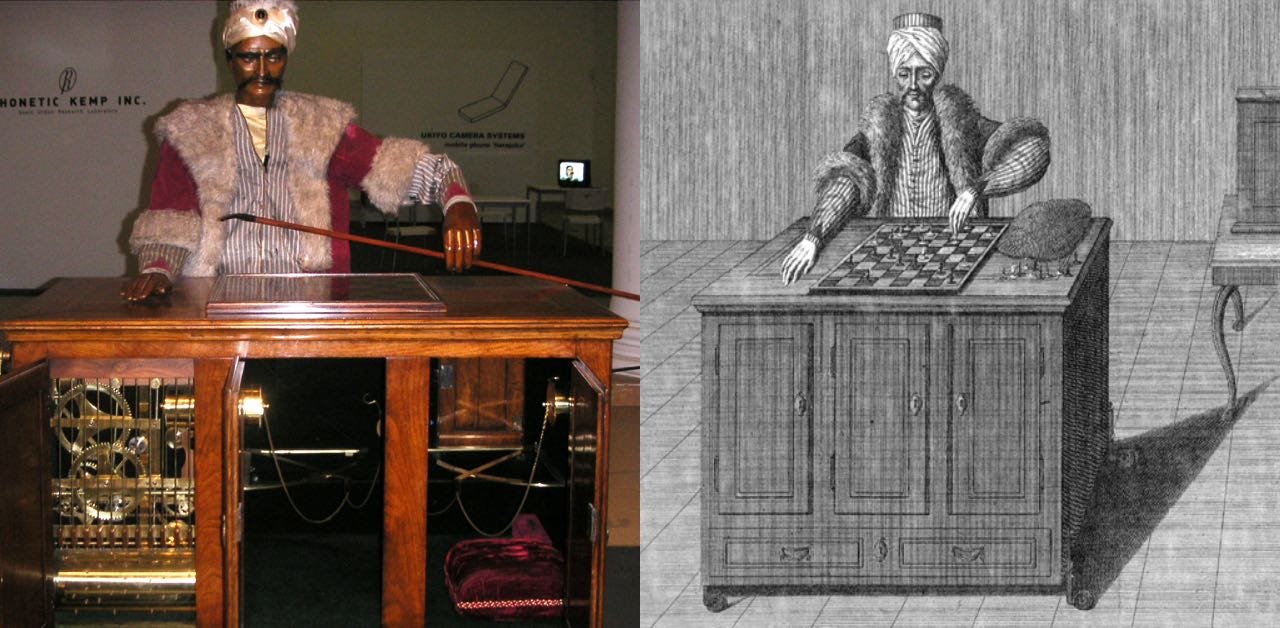

Wolfgang von Kempelen: The Turk (1769)

Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen created perhaps the most famous (and controversial) automaton in history: “The Turk”—a maple wood box with a mannequin that appeared to play chess against human opponents.

How It Worked (officially):

The Turk sat at a chess table

When you made a move, the Turk would move his arm and make a counter-move

It played chess well enough to defeat famous players, including Benjamin Franklin

The Mystery: For nearly a century, people debated whether The Turk was truly autonomous or controlled by a hidden operator. (Spoiler: it was operated by a hidden person inside the cabinet, revealed after Kempelen’s death.)

Why It Matters Anyway: Even though The Turk was a hoax, it was the most important hoax in robotics history. It raised crucial questions:

How do you know if a machine is truly intelligent?

What’s the difference between automation and performance?

Can a human be so well-hidden that we can’t detect their presence?

These questions led directly to Alan Turing’s Turing Test (1950), which asked the same fundamental question: “If a machine can convince you it’s human, does it matter if it’s actually conscious?”

Cultural Impact: The Turk became a symbol of ambition and mystery. It inspired countless stories, inspired debate in scientific circles, and demonstrated that the public was fascinated by the idea of intelligent machines.

The Jaquet-Droz Automata (1770)

Swiss clockmakers Pierre Jaquet-Droz and his son Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz created three extraordinary dolls, each with a unique function:

The Writer: Could dip a pen in ink and write up to 40 characters with perfect penmanship

The Musician: Played music on a harpsichord while her head and eyes moved

The Draughtsman: Could draw four different pictures using a mechanical stylus

The Engineering: These weren’t simple wind-up toys. They were sophisticated mechanical computers, with hundreds of moving parts precisely coordinated.

Surviving Legacy: Unlike many historical automata that were lost, the Jaquet-Droz dolls still exist and are preserved in the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Geneva. They still work.

The Principle: The Jaquet-Droz family understood that precision and reliability were more impressive than speed. Their automata moved slowly but performed their tasks flawlessly. This philosophy—quality over speed—remains relevant in modern robotics.

Friedrich Kaufmann: The Mechanical Musician (1810)

German inventor Friedrich Kaufmann created a mechanical trumpet player—a figure of a man about 180 cm tall dressed in a Spanish costume.

What Made It Special: This wasn’t just playing a pre-recorded tune. The android could simultaneously blow two different tones, demonstrating breath control and the ability to manage multiple actuators (air flow, embouchure, finger position) in coordination.

Thomas Edison: The Talking Doll (1877)

America’s greatest inventor, Thomas Edison, created the Talking Doll—a children’s toy that played nursery rhymes using phonograph technology.

Key Details:

Invented in 1877

Introduced to market in 1890

Used Edison’s phonograph technology

A mechanical doll that could reproduce recorded sound

The Reality: Despite Edison’s fame and the novelty of the invention, the Talking Doll was a sales failure. Why? It was too expensive, fragile, and the recorded sound quality was poor. But failure didn’t matter—Edison had proven a principle: machines could store and replay human communication.

Legacy: The Talking Doll was the first toy robot and a precursor to all voice-enabled robots today, from Alexa to Siri to advanced humanoid robots with speech synthesis.

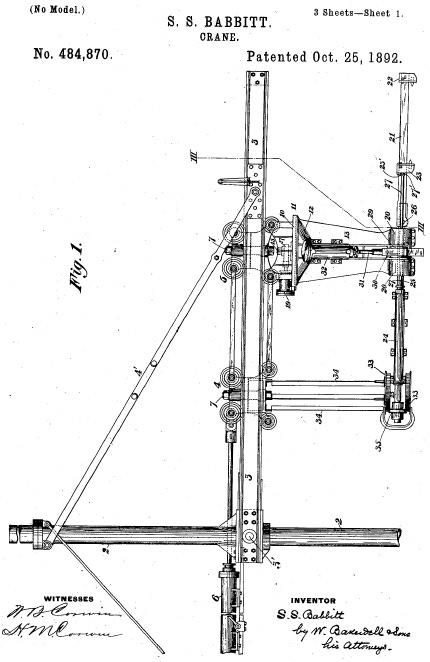

Seward Babbitt: The Industrial Robot Arm (1892)

Seward Babbitt of Pittsburgh patented a rotary crane with a motorized gripper—designed specifically for removing hot ingots from furnaces.

Why This Matters: This wasn’t an entertainer or a showpiece. This was pure functional robotics. Babbitt was solving a real industrial problem: workers were getting burned. A machine with a gripper could do this work safely.

Historical Significance: Babbitt’s rotary crane was one of the earliest industrial robot arms, predating Unimate by 62 years. It proved that robotics could be practical, functional, and essential to industrial safety.

Connection to Modern Robotics: Every industrial robot arm today—from welding robots to surgical robots to manufacturing robots—traces its lineage back to Babbitt’s gripper.

🎨 Leonardo’s Robotic Knight

Around 1495, Leonardo designed a mechanical knight that represented an early blueprint for humanoid robotics. His notebooks, rediscovered in the 1950s, contained detailed drawings of a machine that could:

Sit up independently

Wave its arms

Move its head and jaw

Open and close its visor

What’s remarkable? Leonardo’s design was so efficient that when roboticist Mark Rosheim built a prototype in 2002 using da Vinci’s blueprints, it could walk and wave – proving that da Vinci had designed every component with purpose, with no unnecessary parts. Rosheim later used these principles for NASA robots.

Key Insight: Leonardo’s robotic knight wasn’t just fantasy – it was engineering genius centuries ahead of its time.

🔧 The Industrial Age (1920s-1950s)

The Term “Robot” Is Born (1921)

The word “robot” entered our vocabulary through Czech writer Karel Čapek’s play “R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots”. In his fictional factory, thousands of synthetic humanoids worked so efficiently that they reduced production costs by 80% – a theme that would define the 20th century.

Early Humanoid Robots (1928)

Eric, one of the first humanoid robots, was exhibited at London’s Model Engineers Society exhibition. Invented by W. H. Richards, Eric was revolutionary:

Aluminum body with 11 electromagnets

Powered by a 12-volt power source

Could move hands and head

Controlled via remote control or voice commands

Could deliver speeches

Eric and his “brother” George toured the world, capturing public imagination about what machines could achieve.

1928 - Gakutensoku, Japanese for “learning from the laws of nature”), the first robot to be built in Japan, was created in Osaka in 1928. The robot was designed and manufactured by biologist and botanist Makoto Nishimura (1883-1956). Nishimura had served as a professor at Hokkaido Imperial University, studied Marimo and was an editorial adviser to the Osaka Mainichi newspaper (now the Mainichi Shimbun).

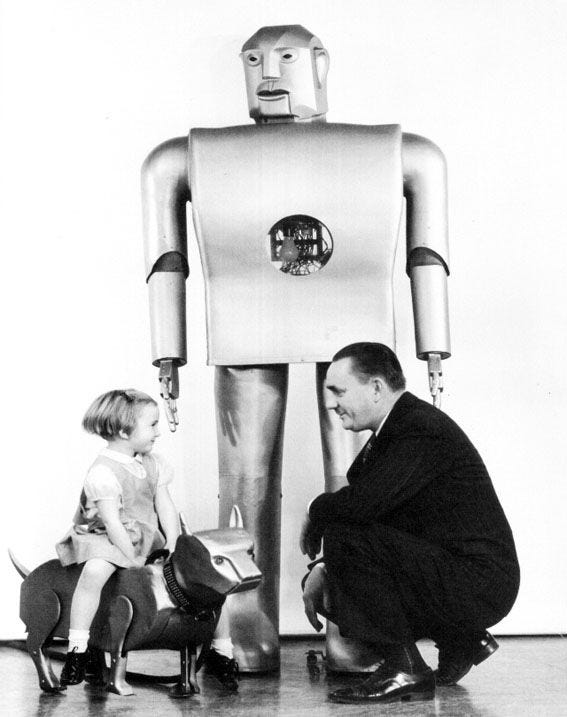

Elektro the Robot (1939)

Westinghouse unveiled Elektro, a robot that could:

Walk independently

Respond to spoken commands

Smoke cigarettes (yes, really!)

Perform various entertainment tasks

Elektro represented the optimism of the pre-war era about automation and the future.

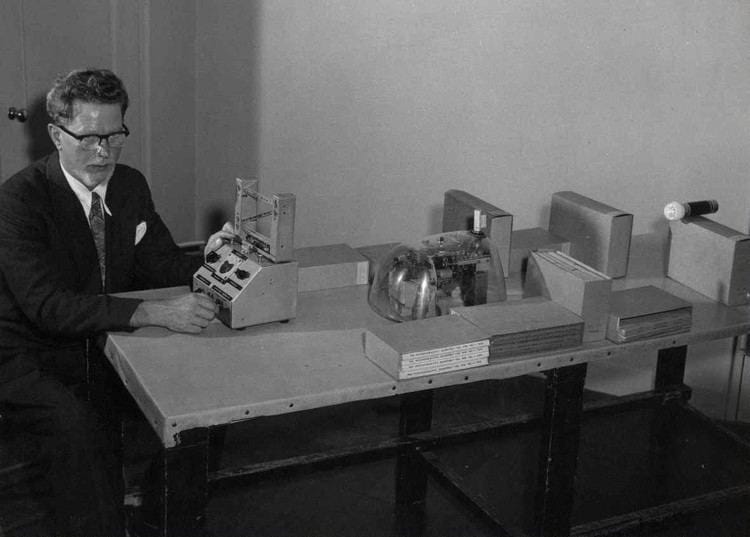

Theoretical Foundations (1942-1950)

1942: Isaac Asimov published his famous Three Laws of Robotics in the short story “Runaround,” establishing ethical frameworks for fictional robots

1948-1949: William Grey Walter created Elmer and Elsie, battery-powered “tortoise” robots that demonstrated early AI concepts

These tortoises could navigate around objects

Find light sources autonomously

Return to charging stations using sensor feedback

Used the foundational technologies still crucial today: sensors, feedback loops, and logical reasoning

1950: Alan Turing proposed the Turing Test, a measure of machine intelligence

1951: Ray Goertz patented a teleoperation arm for handling nuclear materials – practical robotics for dangerous work

🏭 The Modern Robotics Era Begins (1950s-1970s)

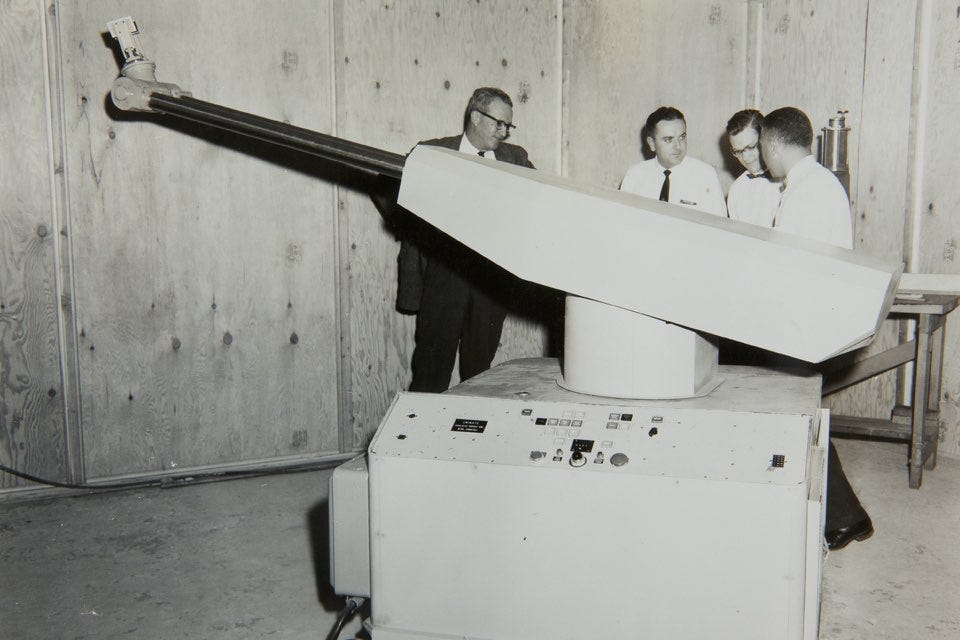

The Breakthrough: Unimate (1954)

The moment that changed everything came in 1954 when George Devol, an inventor from Louisville, Kentucky, filed a patent for “Programmed Article Transfer” – introducing the concept of Universal Automation (Unimation).

What made Unimate revolutionary?

It was the first digitally operated and programmable robot

Hydraulically powered articulated arm

Could store and execute commands

Designed for repetitive, dangerous industrial tasks

The Partnership: In 1956, Devol partnered with engineer and entrepreneur Joseph Engelberger to found Unimation, the first company dedicated to robotics. Their mission: bring automation to industries where workers faced poisoning, burns, and injury.

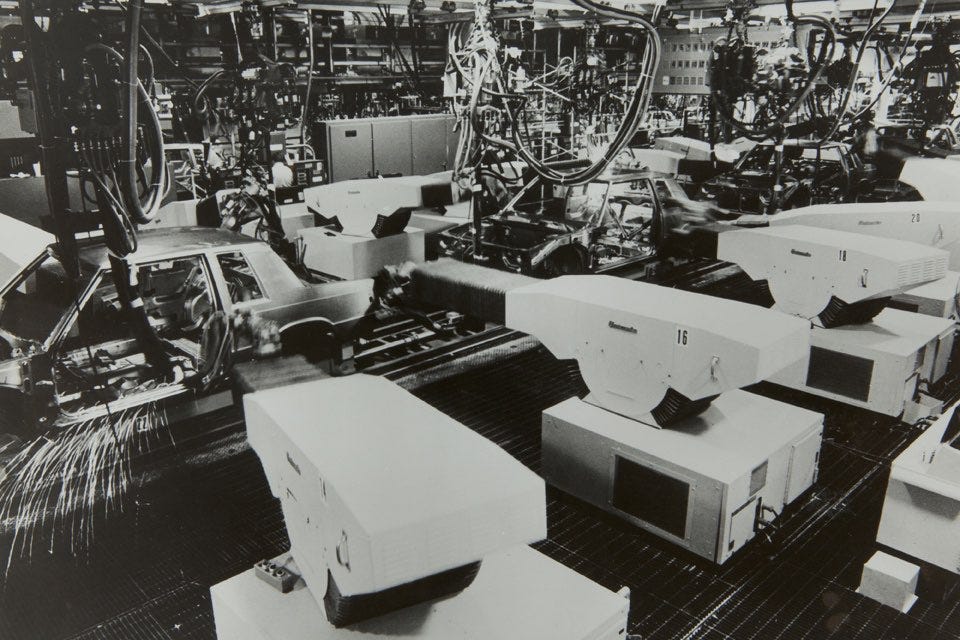

Unimate on the Assembly Line (1961)

On June 3, 1961, the first Unimate began operations at General Motors’ Inland Fisher Guide Plant in Trenton, New Jersey. Its job: lift hot pieces of metal from die casting machines and stack them – work that had previously endangered workers.

Impact: Unimate revolutionized automotive manufacturing, proving that robots could work 24/7, perform dangerous tasks, and improve productivity without fatigue.

Production & Growth: By 1966, after years of field testing, Unimation began full-scale production. Other applications followed: welding, materials handling, and assembly. The company achieved profitability by 1975, validating the entire robotics industry.

The Evolution (1960s-1970s)

1966: The Stanford Research Institute developed Shakey, marking the next frontier – mobile robotics with artificial intelligence. It’s the world’s fist mobile intelligent robot.

Shakey could:

Reason about its actions

Analyze visual information

Plan routes while avoiding obstacles

Execute complex goals like “go to room D and push block 9 over to doorway 4”

Use the groundbreaking A* algorithm for pathfinding

This algorithm, developed for Shakey, is still used today in GPS navigation, text analysis, and video game AI.

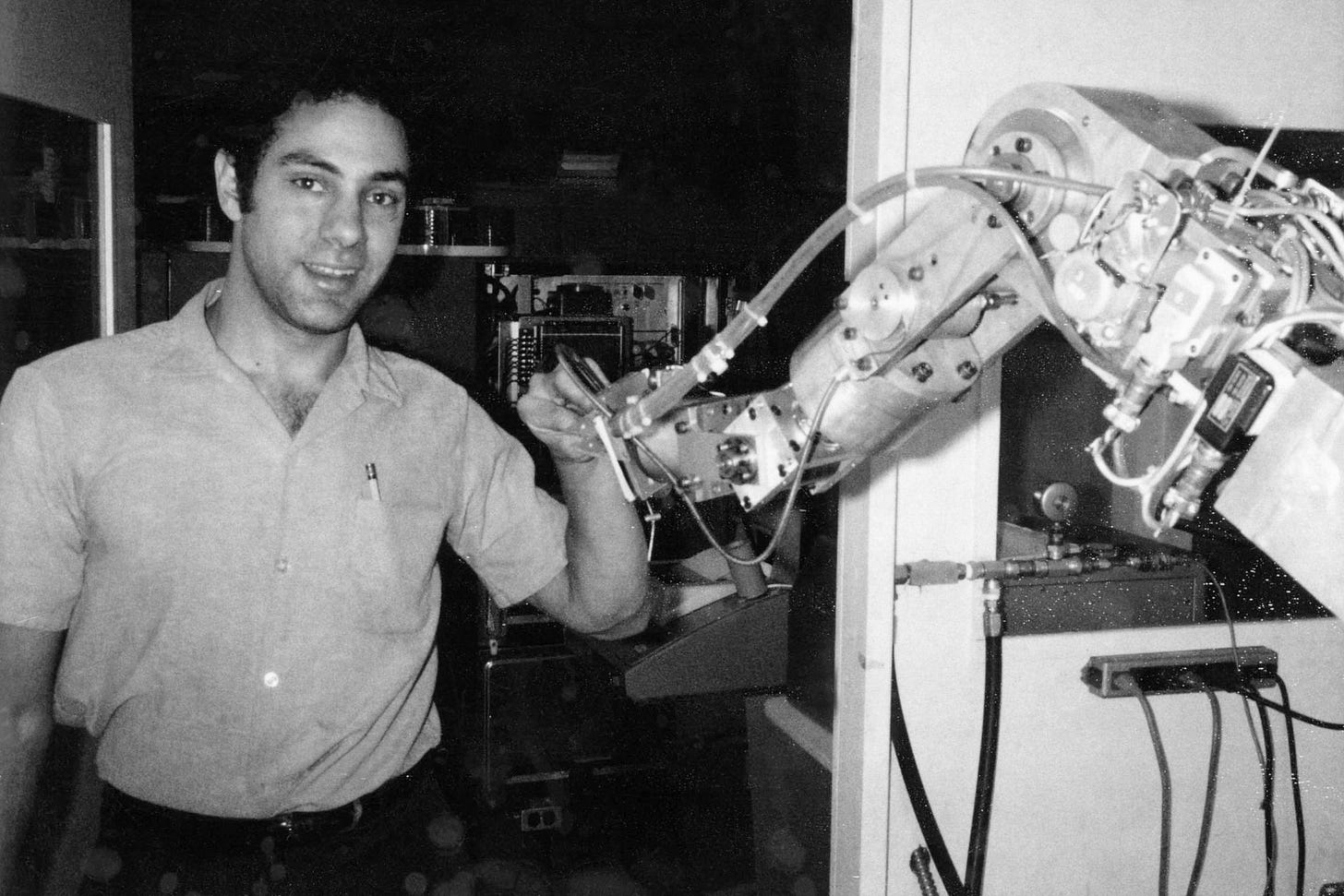

1969: Victor Scheinman designed the Stanford Arm – the first small, electric-powered six-axis robot. Unlike Unimate’s hydraulic system (which leaked and limited placement), the Stanford Arm used electric motors embedded in the arm itself, enabling:

Faster movement

Cleaner operation

Greater versatility

Wider industrial applications

1972: The first robot using artificial intelligence emerged from Stanford Research Institute, advancing machine reasoning capabilities.

1979: James L. Adams created The Stanford Cart, one of the first examples of an autonomous vehicle in 1961. In 1979, the vehicle successfully moved without human intervention in a room filled with chairs, reaching speeds of up to 55 mph without any obstacles or human drivers.

1984: Wabot-2, a humanoid robot capable of playing keyboard and reading musical scores, demonstrated how far robotics had come in two decades.

🚀 What’s Next?

That wraps up this edition. Stay tuned for Part 2 in our next issue, where we’ll unveil the next frontier in robotics innovation.

📢 Share Your Thoughts

What aspect of robotics history fascinates you most? From Leonardo’s mechanical knight to Unimate’s industrial revolution, robotics has always represented humanity’s drive to create and innovate.

Drop a comment or reply to this newsletter – we’d love to hear your perspectives!

Think Stack 101 — Your Daily Stack of Knowledge, Wisdom, Ideas 🧠

Cut through the noise!

Follow Think Stack 101 on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, Telegram, and Substack for your daily stack of knowledge, wisdom, ideas, and innovation to power up your thinking. 🚀🧠✨

✨ One smart thought a day. Just the boost your mind needs.

What stands out here is how old the core robotics problems actually are - feedback loops, coordinated movement, programmability. Ctesibus solving self-regulation in 270 BC with water clocks basically invented the thermostat 2000 years early. The jump from Vaucanson's performance automata to Unimate is less about new concepts and more about better actuators and control systems. I think the most underrated part of this history is how Babbitt's 1892 industrial gripper predated Unimate by six decades but nobody noticed becuase it wasn't packaged as a "robot." The framing matters as much as the tech sometimes.